At Halloween, every neighborhood has one, doesn’t it?—either the Witch’s House, or the Haunted House. This Halloween, my wife Alex and I did what we do every year and joined our friends Mike and Lisa to scare the hell out of our Douglas Manor neighbors and their children at the Witch’s House. Amazingly, it works.

The witch sizes up the crowd as they file up the bluestone path—who will she scare the most?? Skulls hang on the front door and bats and skeletons hang from the trees. Even the flower pot gets a jaunty skull to set off the blood red.

The phrase “Come here my pretty” spoken by Lisa has reduced several small children to tears, running back to their parents in abject fear. Same with some of the parents who have been ambushed while fellow Halloweeners—myself, Alex, and our friends Kathy and Nancy—distract at the front door with less frightening visages while Lisa sneaks up from behind, or leaps out of the shrubbery.

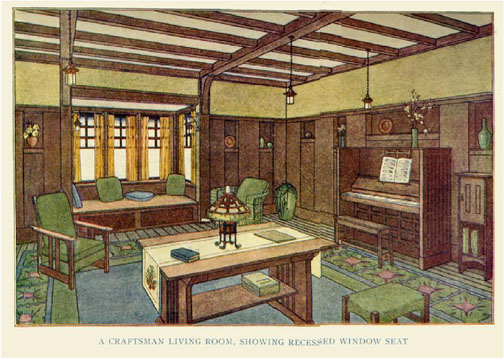

The Witch’s House looks pretty normal most days—a 1926 English cottage style house with a sloping “cat slide” roof over the sun porch, and a cheery and welcoming red door. I designed the restoration and renovation for Lisa and Mike more than a decade ago, and I love seeing how they put this house through its paces for the life they live, including on Halloween, a high holy day in their canon of life’s important events.

Lisa is a very ugly witch with green tinted skin and rotting teeth, who ramps up her theatrics with a boom box hidden in the bushes that amplifies and echoes her voice to great effect. Her voice stops them in their tracks before they even get to the front door.

An ancient crooked redbud tree frames the Witch as she returns from scaring away children—but not until they get their candy. Mike varies his act each year. Sometimes he is a mirror-faced cipher—scary in and of itself—or a skeletal monster, like here.

This year he was “himself,” cheerfully handing out candy to the kids while wearing a flannel shirt and jeans.

I love seeing the costumes the kids wear, a reflection of culture, fantasy and sometimes the truly weird. Some of the parents are more terrified of the Witch than the kids. And some have better costumes than their kids!

Are you thinking scaring kids is a little bit mean? Not at all. Every kid likes a little frisson with their candy on Halloween. Several mini ghouls and comic book characters were overheard Halloween night as they approached saying, “Here it is—the Witch’s House! It was really good last year!” And next year we know, they’ll be back for more! Ow Ow-oooooo!!

Our backyard neighbor’s mutts are transformed for Halloween into “Dino Dog” and yes, a peacock!

The Pee Wees arrive in force—a variety of costumes on display. Fairies and Flamingos and Spiderman.

A yellow dinosaur attempts a backward glance—a fail! A wee Batman has backup with The Cat in The Hat. Where’s the Joker?

Waiting for the “Reveal”—will she be as ugly and scary when she turns around as my friends said? Mike hands out candy in the background—an exotic young girl from some far away kingdom heads back to score more candy.

For some, visiting the witch is just another photo op. The adults are having fun too!

A zombie Woman in White quietly decomposes… who is she eyeing next? Oh what a tangled web we weave—on our hands?

Some Halloween transformations are subtle—Alex grows black velvet horns for the evening, and wears her favorite gold spider necklace and matching earrings. In a previous Halloween incarnation, Alex as Young Dr. Frankenstein.

The mysterious zombie Woman in White forges an alliance with the Witch—will it last? Zombies are never satisfied for long.

Uh-oh, the pizza’s late! Will they have Mike for dinner? Tools of the (Witch’s) Trade—blood stained eyeglasses, a microphone at rest and a Vampire’s Blood Cocktail signal the end of the evening.